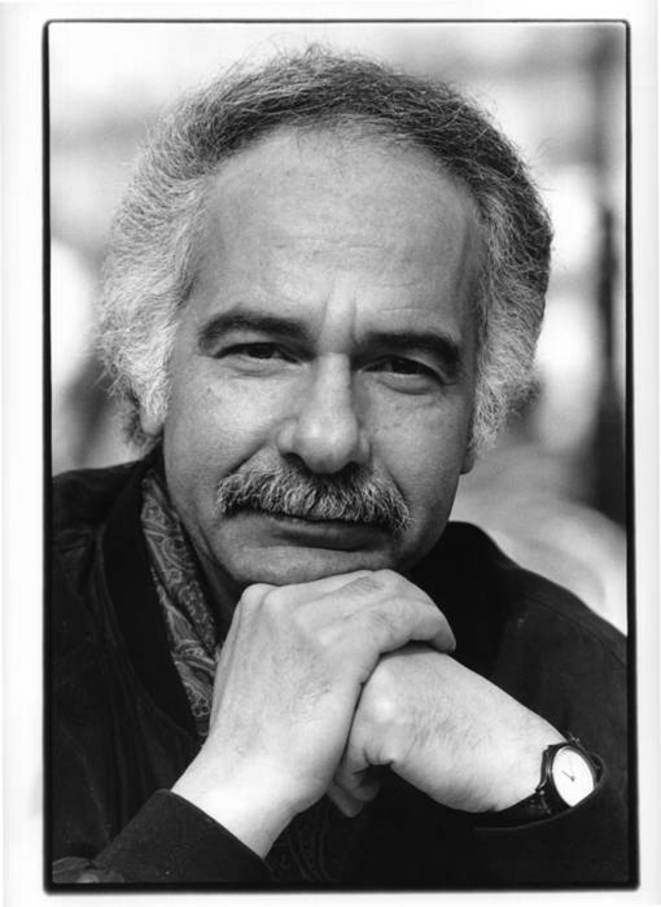

Abdelatif Laâbi

Créteil, August 2010.

The Moroccan cultural scene offers an unusual curiosity … in other climates. It is not customary, when presenting the work of one of our creators (painter, poet or other), to speak of the man (or of the woman), to take into account the process of his intellectual training, his life experience, including intimacy, a fortiori the traits of his temperament, his sensitivity. His ideas are also deadlocked, whether they concern the conception of his artistic practice or his perception of the problems of his own society and of human society in general. As a result, the risk is taken to send back the image of a pure spirit, whose only proof of life is limited to the finished work, delivered to our appreciation. What precedes, the genesis if you will, and what happens during the clinch with the canvas, the blank page, escape us most often. And how would we know if nothing is reported to us of the man (woman) in question, the flesh and blood being whose consciousness emerged at some point in history, whose seemingly peaceful life or manifestly tumultuous was marked by the particular of its meetings, discoveries, loves, obsessions, dreams, visions and struggles? So many elements that have shaped his character, affirmed his choices and constituted, sometimes reluctantly, what is commonly called his destiny.

For the sake of my lifelong friend, the companion of ordeal that Mohammed Chabâa was for me, but also the artist I admire because he literally “opened my eyes” to the world of painting, I had to remember these prerequisites as his life embraces and illuminates his work, and it gives an account of his life with exceptional fidelity. The debt that I am trying to express here is only a part of the immense debt that Moroccan culture as a whole will one day have to honor towards him. To stick to what I was able to observe during our companionship, I would say that, without him, the experience of the review Souffles in the sixties would not have made the spectacular advance towards modernity that it is undoubtedly recognized today. The futuristic shape he managed to imprint on it had, rare thing, a real impact on the content itself. Thanks to him (and to the other painters in the review), the rehabilitation of our traditional arts has led us to seek popular heritage in all its diversity to make it one of the levers of the reconstruction and renewal project of our culture.

From this period also date his interventions in public space, his first achievements in the field of the integration of plastic works in architecture, his plea to establish the bases of a visual culture guaranteeing education and taste transformation. Little focused on theoretical abstractions, even if, among our great painters, he is the one who wrote the most, he had a practical thought. An outstanding teacher, Chabâa had a keen sense of the steps to be taken and the course to take, the horizon to reach.

From our first meeting, I knew that he was going to be part of what I call my fraternal constellation. I felt in the presence of a quiet force, of a gaze that carries far, towards the outside of oneself as well as within. On the rare occasions when I had the chance to catch him working, I was struck by his hands among other things (and it is true that the hands fascinate me). Quite thin and small for a man of his size and build, they radiated a concentrate of energy and were only worn on the canvas to materialize in a series of learned and delicate caresses what had been designed, long matured beforehand. . And the poet in me jealous the painter for being in such a sovereign mastery of his art. I took note of it! During the time we spent together in prison (1972-1973), we were mostly in the same cell, side by side. Not having the adequate material to paint, Mohammed drew relentlessly with the means at hand (felt-tip pens and colored pencils), preparing the new advance that his work would experience after its enlargement: a vibrant hymn to freedom, a revival of light. interior, carried by a contained lyricism, without the least facility or embellishment.

Subsequently, and for the reasons that one can guess, I followed from time to time his activity. But the few echoes I received from her, the exhibition catalogs that have reached me have always reassured me about what I consider to be the constants of her approach: the sense of responsibility and solidarity, that of pedagogy, the promotion of ethics with regard to the problems of the City or artistic practice. I had pleasure, blowing on the ashes of time, to find in my traveling companion this burning embers of constant questioning, questioning and exploration. Our relatively recent reunion finally allowed me to follow firsthand what the separation and then the estrangement frustrated me. The work of Chabâa, which has been returned to me in its entirety, shines in my eyes by the strength of its achievements, its scale and its scope. I am tempted to use to qualify it a term which is usually used to designate poetry when it narrates the exploits of a character braving opposite destinies to achieve an ideal and achieve full humanity. The term is that of “gesture”. Yes, why skimp on words? Should we only employ the great when they are decreed elsewhere and impose themselves on us by authority? Are we doomed to be removed from it because of I do not know what curse, what original blemish? Would it be overdone to say of Mohammed Chabâa that he was the bearer for him and for us of a Promethean project? No, quite the contrary. I can safely say that his work is an uninterrupted narration of this project, with a singularity however. Chabâa’s gesture has a dramatic note, because she has been constantly upset by the lack of regard for culture and creators in our country. So the inner exile has no secrets for him, and he lives it with dignity, in total discretion. In the manner of Sisyphus (another big word, on purpose), he does not stop carrying his rock at arm’s length. Except that this Sisyphus from here is a painter, knowing better than anyone that the more resistant the material, the more tenacity is needed to distill the essence of his dreams, to transform it into a work of beauty, to go beyond his limits and to exorcise the woes of the world. And the quest continues. More than half a century!

The work of Chabâa is in perpetual movement. It is carried by a course which is anything but that of a quiet river. Sometimes just dripping, sometimes dismantled, it also sometimes disappears under the rock to reappear further on in a new landscape where the finely veiled light reveals an unexpected depth of colors, the imperceptible movement of shapes, the discreet signs of the spirit of the seasons. Throughout this course, stops are indicated, and even the perilous passages where the temptation to break up was strong. Chabâa does not try to confuse the walker or the explorer. He willingly takes him by the hand to keep him away from the beaten tracks and dead ends. His canvases let it be heard like a whisper. Yes, a whisper! audible for those who still know how to exercise this eye of the heart which tends to wither and die out nowadays. The most recent of these paintings that Mohammed made me discover last May at his home deserves even more this extreme attention. At first glance, one would be tempted to detect an unusual desire for a clean slate, or even a provocative snub aimed at “specialists” and merchants of the temple of art who might exclaim: “But where is his mastery? proverbial, its stripping, its polished, its rigorous constructions, its well-framed colors, without smudges? Let us leave this jargon aside, and return to the works, inseparable from man, his demands, his wounds and his questions. Perhaps then we would discover that these paintings express for the first time and without false modesty his fragility and, why hide it, his anguish in the face of the finitude of life and human works, the uncertain fate of the trace that a whole each legitimately aspires to leave behind – especially in a country where one hardly cares about this kind of trace, except when it can acquire a market value -, also in the face of the disorder of the world and the uncertainties that weigh on the future of the human species. When I express this feeling of mine, subjective it goes without saying, thinking of what I will call the obverse of these works, I do not lose sight of their place. There, I like to say that what I have captured makes Mohammed closer to me. Here is an artist who has nothing more to demonstrate, who could let himself flow quietly in the path he has traced and stick to a reassuring trademark for his audience. Yet he takes the risk of destabilizing while remaining true to himself. He does not shrink from deconstruction in what would seem to be a headlong rush when it appears to me to be a tearing away from elsewhere, an irrepressible desire to find the first gaze again, when the eyes open on the inaugural morning of the world, on the light with which the sky, the earth, the water, and all the manifestations of life are clothed. A desire to find the first gesture that tries to translate human emotion in the face of such a miracle. This is how Mohammed Chabâa’s gesture remains open because his horizon is nothing other than the universal inscribed in a culture, ours, which he will have generously marked and will permanently mark with his imprints.

Abdellatif Laâbi, born in Fez in 1942, is a Moroccan poet, writer and translator.

No responses yet